Jenkins Johnson Gallery is pleased to announce a solo presentation of Ming Smith at Frieze Masters, October 2-6, 2019, Booth H14. Smith will present rare vintage photographs from the 1970’s to the 1990’s including works from her August Wilson Series and Invisible Man Series, alongside works from her international travels.

Over the course of her career, Ming Smith, has created an extensive oeuvre, cultivating a gaze which weaves her subjectivity around plays of light, shadow, and intrigue. She has gathered accolades along the way, such as becoming the first Black female photographer to have her work collected by the Museum of Modern Art. Her work is in collections including, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Detroit Art Institute, the Virginia Museum of Fine Art and the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C

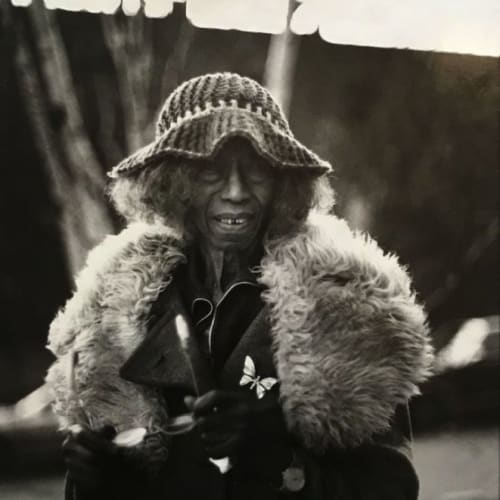

Smith’s August Wilson Series was entirely shot in Pittsburgh, PA, Wilson’s hometown. Rendered in her signature, intimate style, using the natural warm breath of photographic film to propose that her subjects and images are part of her own formal play. Characters are both a memorial to those in Wilson’s plays and as her own symbols of power, care and reflection. “Wilson made marginal people monumental,” Smith says. “Just from going to his plays, I felt so strongly about those characters. When I grew up in Ohio, these were characters I knew.”

Inspired by the groundbreakingly intimate collaborative work by Roy DeCarvara and Langston Hughes, The Sweet Flypaper of Life (1954), one day Smith boarded a Greyhound bus from New York to Pittsburgh to meet with August Wilson’s sister. Wilson’s sister showed Smith the spot where the author would write, nurse a cup of coffee for hours and eventually deem his “dreaming place.” Smith visited other local spots (a diner, Wilson’s neighborhood), capturing Wilson’s plays and life in what would become her August Wilson Series.

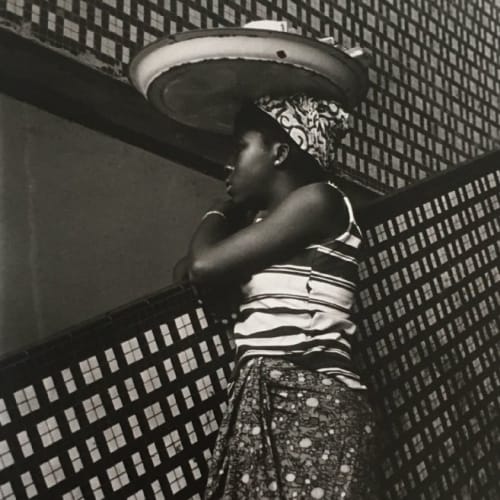

A few years later, Smith captured Harlem, New York. Borrowing its title from Ralph Ellison’s masterpiece, Invisible Man (1954), Smith explores feelings of invisibility and agency through her surrealist imagery. Through her emphasis of light, shadow, mist, and darkness, Smith visually wrestles with the struggle for Black visibility in a culture where the Black experience is systematically policed and violated. In 8x10 prints, Smith’s polyphonic black and white images vibrate with the hum of early 1990’s Harlem. Like many of the works in the series, Little Brown Baby wif Spa'klin’ Eyes (1991) captures a fleeting moment filled with possible narratives and ambiguous figures.

Smith has created a fertile ecosystem which fuses her love of the human experience and her travels with her extraordinary, unique eye. There are echoes of Édouard Glissant’s ideas of opacity that Smith activates in so many of her images through her obscured faces, layered images and lingering vistas. Smith suggests through her photographs that another person is only known when there is enough room for them to identify themselves. In the space left for this identification, there is also implied an endless form of not knowing and it is in this in-between that one finds a meaningful, necessary line of poetry: to see is a form of care. Smith’s photographs in their nuanced lyricism show us, as Smith states simply and elegantly: “it takes time to really see.”

Born in Detroit, raised in Columbus Ohio, and a graduate of Howard University, Smith moved to New York soon after finishing college, working as a fashion model pushing racial boundaries with other talented models like Grace Jones. In the early 70’s Smith became the first female member of the decolonizing and groundbreaking Kamoinge collective: a Harlem based group of Black photographers whose mission was to show the boundless beauty of Black life. Smith worked alongside Black photographic greats like, Roy DeCarava, Gordon Parks and Louis Draper. While Komainge was known for its documentary style, Smith’s work is something else. At times dreamlike, surreal and contemplative, Smith’s photographs find dialogues with manifold mediums while still remaining necessarily, adamantly her vision. These guiding philosophies regarding photography weave throughout multiple series of Smith’s.